This preconception of the art world is one that appears to have gathered strength over the past century as art, or at least its cutting edge, has moved steadily away from strictly representational art.

|

| Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway Oil on canvas, 1844, JMW Turner Bequest to the National Gallery, London |

In the nineteenth century, when artists such as Joseph Mallord William Turner and the French Impressionists stepped away from strict representation, a degree of explanation was needed to educate viewers to a whole new way of not just painting, but of looking at the world. In the twentieth century, when representational art was overtaken by non-representational art, the radical ideas of the Impressionists were advanced ever more radically. In this new and non-representational art, there was no longer a clearly defined subject and so longer explanations were required. Or perhaps the artists, curators and other full-time denizens of the art world simply felt them necessary, in order to justify themselves.

Over the course of the previous century, those explanations became longer and longer. With time, art moved on again, from the non-representational with an explanation to, more or less, simply the explanation. This two-century move from what once may have been perceived as little more than a pretty picture, to something with almost no aesthetic appeal and a long explanation, has served to turn art into an intellectual pursuit. As such, its potential mass appeal has been considerably lessened. This may be why the popularity of artists such as Claude Monet and Vincent Van Gogh continues, since arguably they were among the last cutting edge artists to paint more or less representationally.

|

| My bed Mattress, pillows, linens, objcets © 1998 Tracey Emin / Saatchi Gallery |

Yet in the past few years, western affluence has been in a steady decline. This has helped reveal that many other institutions, most notably politics, banking and the media, seem to be reaching a similarly great point of disconnection with the public. For these institutions change has become not just something to be hoped for but something that would seemingly have become unavoidable. In the world of art, change appears already to be underway.

As the traditional methods for the dissemination of knowledge about art have lost either their credibility or their funding, and as with so much of our lives, the internet has taken over. Here is a quiet revolution, where much of the media and countless galleries who continue to peddle artistic alienation are being left for dead.

|

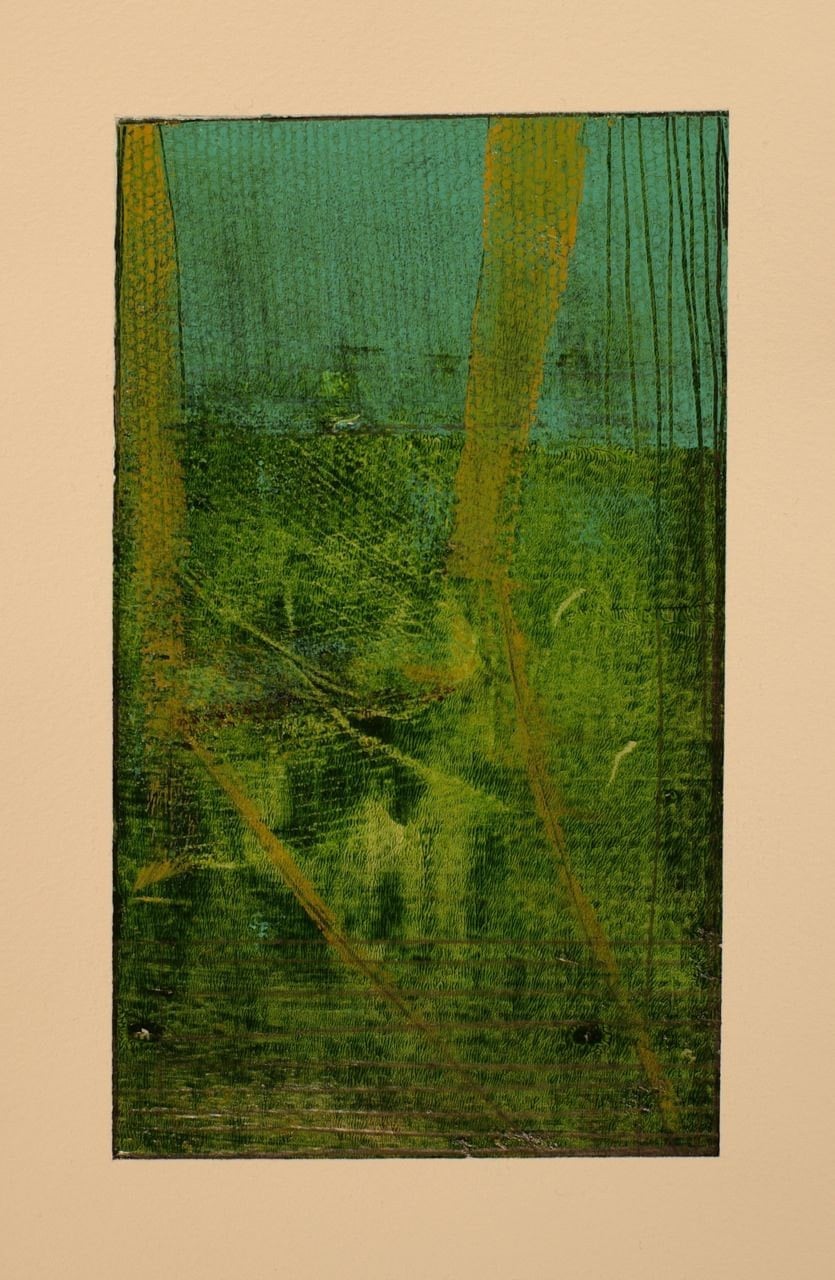

Dissolution chemistry

Mixed media on paper © 2009 Megan Chapman |

I saw a painting I liked in an Etsy store, made by someone I knew only slightly (then) through a social media site. I liked it and realised that since it was a small paper piece, I could afford to buy it. This simple access to original art was a revelation. I saw how easy it was to own art and quite possibly always had been. For the life of me, I could not understand why I had never bought any before. So it was that with one or two mouse clicks, I became the owner of a piece of original art. In the time since then, I have bought (and traded) several more pieces of art and now have a collection that includes the work of more than ten artists. Buying art, I now realise, is like buying anything else. There is no great drama to it, no need for endless pondering or justification. If I see a piece that I like, I can simply buy it, or else negotiate payments or a trade. It is simple knowledge that I wish I had possessed for so much longer.

While most of these pieces in my collection are small, they are indistinguishably real and original art and they are on my walls. To sit among them is an indescribably pleasant feeling. I know each of the artists who made the work and so feel a personal connection to the pieces. I also feel that here, finally, is something permanent in my life, something that will with luck out last me and that perhaps some future generation will hold and enjoy and know that it was part of my life.

|

| Uncharted territory Mixed media on panel © 2012 Megan Chapman & Stewart Bremner |